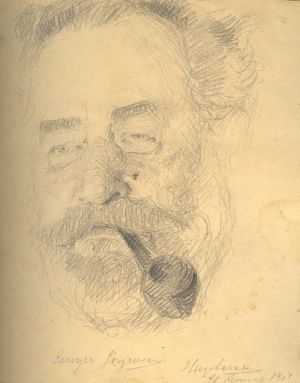

Jens Peter Jørgensen appr. 1875

About the article

This article was originally written in Danish and for a Danish audience. With varying

contents, focus and illustrations it has been published in the Danish West Indian

Society's periodical 2011 nos. 1 and 2, and in Koldingbogen 2011.

The present version, although translated into English, still represents the

original Danish viewpoint.

Anyone who has studied the history of the Danish West Indies, particularly the last 50 years, recognizes the name Lawyer Jørgensen. Reading just a few of the newspapers and written stories of the time leaves an impression of a well-known and respected, but also deeply controversial person. He interfered heavily in the business life and politics of the islands. He was a speculator in land properties and plantations, but gave land away for free to people in whom he believed. He was appointed Knight of Dannebrog for his altruistic efforts as public trustee, but later came extremely close to being convicted for treason by the US authorities after the Transfer in 1917. He was a wealthy man, but ended up bankrupt. He lived for 40 years more or less separated from his family and yet he managed to keep the family close together. In short, a complex person deserving a biography.

Jens Peter Jørgensen was born in Kolding, a provincial city in Jutland, Denmark. He was the ninth and youngest child of a family in which the father had a liquor factory like his father before him. But Jens Peter's father had wider interests. He later became host of a local club and involved himself as a local politician for 12 years. In his last decade he served as a master of the hospital of Kolding. Jens Peter's mother could trace her ancestors back to medieval families in Kolding.

Jens Peter started in the local school, but already at the age of ten years was moved to the Latin school in Haderslev where his older brother-in-law, Conrad Iversen, served as a teacher. But Jens Peter never graduated. After the war in 1864 in which Prussia invaded and annexed Schleswig-Holstein, the Latin school was closed. Instead, Jens Peter studied law in Copenhagen and took a bachelor degree in 1867. He returned to Kolding, where he served in the local administration for a few years before being appointed as attorney. In 1871 he married Anne Cathrine Nissen of an old sailing family from Ærø. At this point of time he seemed destined to pursue a local career. By his father's death in 1873 he was even appointed interim master of the hospital. But the permanent job as master was given to a local bookseller.

Was Jens Peter disappointed to be passed over? Or was he just longing to go abroad? Already in 1868 he had done some travelling in North America. Now he made a giant leap, almost literally into deep water. In 1875, he moved with his family across the Atlantic and settled as attorney in St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies. Down to the tropics, to a colony in deep crisis, but also full of challenges.

The colony in the West Indies had been founded in the years around 1660, from the beginning hardly driven by a clear purpose, but the strategy soon became evident with the well-known - and infamous - triangular trade: Weapons and other industrial products were sailed to West Africa, traded for slaves who were then sailed to the Carribean to slave on the sugar plantations whose products could then be sailed back to Denmark. One can easily imagine how profitable this trade was in the 1700s by taking a walk around the royal palace in Copenhagen. Almost all of the mansions in the area were built based on fortunes made in Danish West Indies.

In the latter part of the 1800s, the situation was completely different. The West Indian sugar cane was being driven out by competition from the European sugar beet. The Emancipation in 1848 ceased the easy access to a cheap labour force that could be whipped to work. Thereby, the economic incentive for the colony disappeared. As early as the 1850s, the first of many negotiations started, eventually leading to the Transfer of the colony to the USA in 1917.

Hugo Larsen: Street life in the harbour of St. Thomas, 1907. Private collection.

Jørgensen arrives to a stagnating colony, but there are opportunities. St. Thomas possesses the best natural harbour of the Carribbean, an ideal stop-over for ships passing to and from Central and South America, not only during the time of the tall ships, but also to a large extent for steam ships. There is a lively traffic and trade in St. Thomas and a large international element. But in spite of Charlotte Amalie having one of the biggest populations of all cities in Denmark during the last parts of the 1800s, it is primarily the economic life and only a narrow segment of the population that need an attorney. But Jørgensen is an enterprising person who soon diversifies his activities.

After the Emancipation, the plantation business on St. Thomas had almost ceased. But Jørgensen has the great idea of revitalizing the colony by mechanizing the operation of the plantations. He purchases a number of idle plantations and hires an American engineer to build a complicated machinery for a mechanical sugar mill. He even invites the governor to the inauguration. Unfortunately, the machinery never comes into operation. One may say that this failed project in an almost tragic way marks the end of sugar cane growing on St. Thomas. In retrospect, the hilly landscapes of St. Thomas and other more prosperous job opportunities available in the harbour made it extremely difficult to revitalize an industry that had previously supported not only the colony, but had also created huge fortunes in Denmark. So Jørgensen tries his luck on St. John and St. Croix with varying success, but more persistent effort. On St. John, he owned the well-known properties Annaberg and Enighed for many years. On St. Croix he owned several plantations too, among them for a short period Little La Grange which he soon sold to the well-known Lawaetz family who diligently and cleverly cultivated the soil and built their family dynasty. The main building on Little La Grange is now part of the Whim Plantation Museum. Jørgensen's activities in the plantation business can also be seen in the newspapers. In 1906, he writes an article in St. Croix Avis describing how to collect and preserve rain water for sugar cane growing. Overall, Jørgensen is very active in the property market. As late as in 1918 when he plans to cease his business in St. Thomas, he still owns more than 2,000 acres of land.

Hugo Larsen: Lawyer Jørgensen 1907. Private collection.

For a period he worked as deputy school inspector. He became public trustee and was generally acknowledged for his ability to create order in the administration and accounting. He engaged actively in politics and was a member of the Colonial Council. He took the initiative to the society "The Danish Speaking Club". For a longer period he also worked for the governor's office until he was dismissed due to his outspokenness about the arbitrary and faulty dispositions of the administration. All of this naturally side by side with his core business as lawyer. Among his major customers was Hamburg-Amerika Linie (HAL), for many years the dominating ship owner in the harbour of St. Thomas with its own yard, large headquarters etc.

Jørgensen's political viewpoints and activities are best described in two documents from 1902 and 1916, both pertaining to periods of negotiating the sales of the islands to USA.

From the beginning, Jørgensen was a heavy opponent to the sale. His basic viewpoint was that the colony had great unexploited potential. The problems, though real, could and ought to be solved by a targeted effort to the benefit for the islands themselves and for Denmark. In 1902, when Denmark was about to sell the islands, he published an essay with which he lectured on a tour of Denmark. In the essay, his idealism and enthusiasm are clearly expressed. What is needed, in his opinion, for the colony to recover are topics that he himself is working on, be it plantation organisation and operation, shipping, infrastructure, health service, and education. Both his words and activities are in line with the moral rearmament taking place in mainland Denmark after the shocking loss of Schleswig-Holstein in 1864. It is uncertain how much he was able to influence the general opinion. The Parliament was at the point of approving the sale, had it not been for a questionable vote in the chamber that was partially appointed by the King. But there is no doubt that Jørgensen planted a seed with the nationally minded conservatives. In the years to come, they made a considerable effort to develop the islands and tie the colony closer to mainland Denmark.

In 1916, the situation was radically different. The private initiatives which actually came after 1902 had dried out. The public reforms which had been implemented were too arbitrary, insufficient and mistaken. In addition, World War I had almost put an end to ship traffic on St. Thomas, depriving the colony of a major income. As an elected member of the Colonial Council, Jørgensen was summoned to a meeting in Copenhagen with the commisssion which was to advise the Parliament before the final decision to sell the colony to USA.

The Colonial Council for St. Thomas appr. 1916. From left to right medical doctor

Viggo Christensen, Lawyer Jørgensen and James Roberts.

Foto: Heinrich Petersen. Reproduced with permission from Digital Library of the Caribbean

(www.dloc.com).

Jørgensen has not changed his basic attitude. The islands can and ought to be developed to be self-supporting. This is a work-in-progress on the islands, driven in part by Jørgensen. But the effort by the official Denmark has in his opinion been incompetent, open to criticism and without any understanding of the special conditions prevailing in the colony. With numerous examples, he points out what has not been done and how the implemented reforms have deteriorated the conditions. As he points out, one cannot treat the Danish West Indies as any other county of the country. The conditions are too special, demanding a deep understanding, which has not been in place with the public administration, let alone with the governor Helweg-Larsen, whom Jørgensen accuses for being biased and acting arbitrarily in his decisions. As mentioned, the examples are numerous, but let us confine ourselves to a few. In 1907, the High Court in St. Thomas is abolished. Thereby the islands lose a high-ranking independent official who could moderate the governor when acting at his own discretion. But worse than that, "The poor prisoners had their imprisonment prolonged from 3 weeks to 3 months when their cases were appealed to the High Court. [....] Is that human? Is that an improvement?", Jørgensen asks. He makes sarcastic remarks pointing out that maternity homes have not been built a long time ago to bring down the far too high infant mortality instead of constantly importing a disobedient and rebellious work force from other islands in the Carribbean. In St. Thomas, the West Indian Company has been allowed to build an oil inventory, while Standard Oil's application has been refused, for which reason Standard Oil keeps away from the harbour. It is not a disposition creating growth. What makes it worse is that the governor is chairman of West Indian Company. The few examples mentioned serve to illustrate Jørgensen's deep frustration over the public administration's missing insight in the local conditions and its lack of will to create real improvements. Jørgensen has lost his patience. "The psychological moment is over", he says and warmly recommends the sale of the islands to USA.

And that is what happens. On the 31st of March 1917, the Danish flag Dannebrog is lowered and Stars and Stripes is raised. But one wonders whether Jørgensen has considered the consequences of the Transfer to his own and his family's personal situation?

Family Life

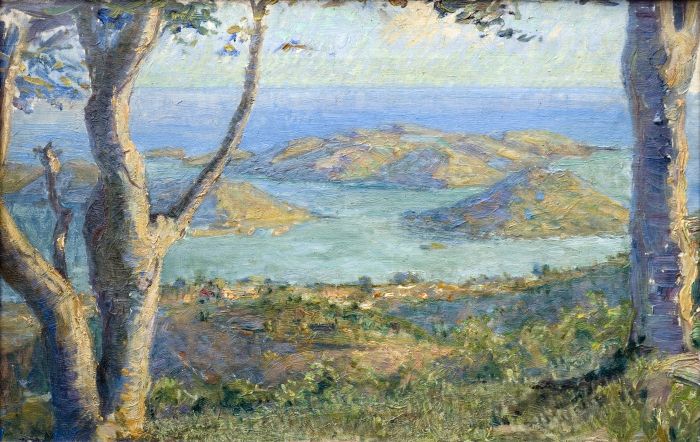

Hugo Larsen: The view from "Mafolie", St. Thomas 1906. Owner: Knuthenborg. Photo: Finn Brasen.

As mentioned, Jørgensen brings his family with him to St. Thomas in 1875. The couple had their first daughter Henriette in 1872. In the West Indies, Anna is born in 1877, and then Andrea in 1878. But Mrs. Jørgensen cannot stand the tropical heat. Jørgensen therefore purchases "Mafolie", a rural estate in the hills behind Charlotte Amalie with the most beautiful view of the city, harbour and sea. Rising approximately 250 meters above sea level with the trade winds blowing unhindered, it's a bit cooler than in town, but not sufficient enough for Mrs. Jørgensen. So by the end of the 1870s she returns to settle again in Kolding, where the fourth daughter Elisabeth (called Lissa and Lizzie by turns) is born in 1880. A couple of years later, Mrs. Jørgensen makes another attempt to reunite the family and their daughter Margrethe (called Baby) is born 1883 in St. Thomas. But it does not last long, and in 1885 Mrs. Jørgensen moves back permanently and settles in Horsens. Here the youngest daughter Christine is born 1886.

After this, Mr. and Mrs. Jørgensen lived apart for the rest of their life, with the exception of the few travels that were possible. One may wonder how a family life could be maintained in that situation, but it was. The letters are many, concentrating not on business, but on everyday life. Jørgensen writes cheerful letters with elements of upbringing to his daughters who in turn are informing each other. A particular pleasure for Jørgensen was that his daughters quite often visited him for extended periods.

Hugo Larsen: Lissa Jørgensen, St. Thomas 1905. Private collection.[1]

Lissa and small Jens Peter Meyn, appr. 1915.

Particularly Lissa seems to have been attracted to the West Indies. She moves to St. Thomas around the turn of the century staying with her father for a number of years. During this period, Hugo Larsen, an academically educated painter visited the West Indies from 1904 to 1907 and painted some of his best works there, including the beautiful portrait of Lissa Jørgensen. She was later married to the German Heinrich Meyn, ship inspector of HAL. The couple had a son in 1913, named after lawyer Jørgensen.

The Disaster

The situation in 1916 is quite complex. The Great War is in its third year, Denmark is about to sell its tropical colony to USA which in turn is close to declaring war against Germany. An explosive cocktail for a Danish family which now has both professional and personal ties to Germany.

In that situation Jørgensen makes two decisions. One is both wise and affectionate, while the other shall prove to be fatal for himself. When he is summoned to the advisory commission in Copenhagen, he brings Lissa and young Jens Peter with him for them to stay with Mrs. Jørgensen and Baby who in the meantime have moved to Frederiksberg, Copenhagen.

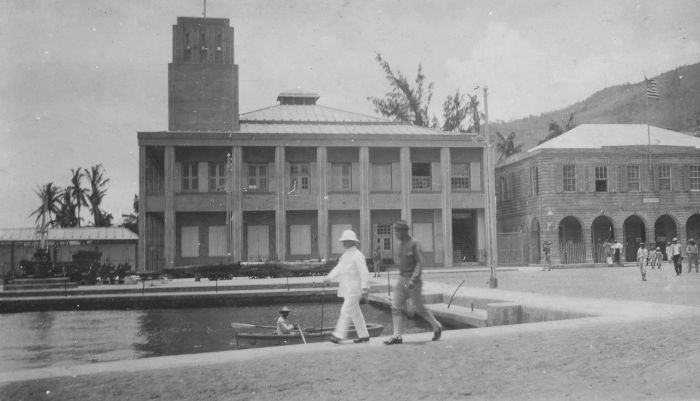

Hamburg-Amerika Linie's headquarter in Charlotte Amalie, appr. 1917.

But after Jørgensen returned alone to the West Indies in January 1917, he entered into a pro forma deal with Julius Jochimsen, the managing director of HAL in St. Thomas. The parties were obviously aware of the fact that all German property within the borders of the USA would be seized when the USA and Germany declared war. They therefore made a contract in which Jørgensen would purchase all of HAL's possessions in St. Thomas (headquarters, quays, yard, coal inventories, barges etc.) for the amount of $210,000. Jørgensen did not have that kind of money for which reason they signed an instrument of debt saying that the debt should not bear interest and fall due after three months, which deadline could be prolonged until the war was over. The purpose was of course to prevent confiscation, after which the parties could agree on a friendly return of the valuables after the end of the war. But shortly after the Transfer and the declaration of war between the USA and Germany, the Alien Property Custodian arrives in St. Thomas. He has no doubt about the nature of the agreement, a pro forma deal which also Jochimsen later admits in a letter to the company's Board of Directors. As a consequence, the Custodian simply confiscates all the property. The only problem is that Jørgensen is not willing to admit to the deal being pro forma. He maintains that the deal is bona fide, made on neutral Danish territory.

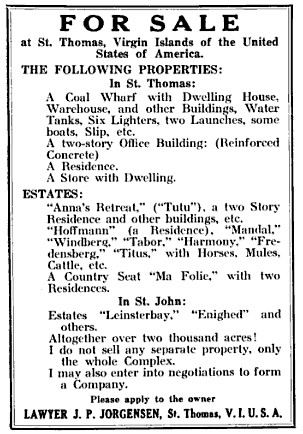

Advertisemnt in Shipping, January 1918

Now a complicated diplomatic exercise commences. On one side the Custodian maintains - rightfully - that the deal is pro forma. On the other side is a Danish citizen who has purchased German possessions on Danish - i.e. neutral - soil. Jørgensen has a detailed insight in the treaty behind the Transfer. The treaty clearly says that USA will respect Danish and other countries' citizens' possessions after the Transfer. Jørgensen involves the Danish ambassador in Washington who in diplomatic terms asks the US secretary of state to respect Jørgensen's right of ownership. Meanwhile, the Custodian tightens his grip on Jørgensen by closing his company's bank accounts in the Danish West Indian National Bank and by bombarding him with requests for the money he has made for the company by selling coal and other goods. What is worse, the Custodian discovers that HAL has left a major credit in Puerto Rico which Jørgensen has drawn upon without informing the authorities, thereby practically placing the loop around his own neck.

In his desperation, Jørgensen proposes to sell HAL's possessions in USA and he offers to sail back to Denmark to raise the money which the Custodian can subsequently deposit. His letters to Ambassador Brun grow more personal and show his increasing distress, naming the world a madhouse which would have been even worse, had Denmark not sold the islands voluntarily.

But nothing helps. The Americans convince Ambassador Brun that the deal is pro forma. Jørgensen receives a sharp letter from Consul General Baumann telling him unambiguously that he will save his personal belongings and avoid being prosecuted only due to the ambassador's diplomatic efforts, not due to Jørgensen's own acts and arguments.

Lawyer Jørgensen and dr. Viggo Christensen in Villa Mafolie, appr. 1925-26[2]

Thus, Jørgensen saved his skin, but not his honour. In July 1918 he unwillingly signs a document, transferring all of HAL's possessions to the Custodian in exchange for being released of his debt to HAL. One may wonder why the Custodian was so keen on having Jørgensen sign the transfer document as the deal had already been identified as pro forma. The reason was the mentioned quibbling remark in the Transfer treaty, protecting possessions belonging to persons and companies resident in Danish West Indies. After the end of the war in 1919, Jørgensen used the same loophole to reopen the case. Now he demanded on behalf of HAL that the possessions should be delivered back to HAL which could then hand them over to Jørgensen against the payment of the said $210,000. He even asked HAL to sue him for the $210,000. Needless to say, these initiatives of his were ignored. At the time, HAL negotiated directly with the US administration, though also in vain.

It is not clear when Jørgensen finally gave in. But there is no doubt that this case was fatal for him professionally. Also his finances had suffered and when he finally returned to Europe, he was forced to take out a loan to pay for the trip. To make things worse on his finances, he settled for some years with the daughter Lissa in Lübeck during Germany's hyper inflation. If he was not ruined when leaving St. Thomas he was now sure to lose what was left. In 1924 he returned to Denmark and settled in Horsens where his wife had been buried six years earlier. He died in January 1926 during a visit to his daughter Henriette who had married Hjalmar Aae, the secretary of the town council in Aarhus. The couple had built their own villa and named it "Mafolie".

Idealist and pettifogger

There is no doubt that Jørgensen during the last years of his life considered himself a failure. He did not realize his dream of developing the Danish tropical colony to be self-supporting. The future under American rule was not as bright as he had hoped. But when we characterize him it will be under different conditions.

He was much of an idealist and a bit of a pettifogger

The shortest and most precise characterization was given in the memoirs by his past trainee lawyer, N.A. Kjær: "He was much of an idealist and a bit of a pettifogger". The idealist and fiery soul made a remarkable effort to develop the Danish tropical colony in a critical period. He worked for free for the cases and persons close to his heart. He took personal risks in the projects he was passionate about. There was a good reason for appointing him Knight of Dannebrog in 1888. On the other hand, the pettifogger showed his face in court cases and property deals where there was money to be gained. When arranging a property deal he would often demand 10% in commission. In some cases - particularly the case about HAL's properties - it is hard to evaluate which part of his personality was prevailing. They lived side by side. Was it the loyalty to his family and biggest customer that ranked highest for him or was it his greed? There are other nuances to his personality. He lived an extremely ascetic life, was very disordered and dressed untidily. But when we balance his account, the idealist stands. He made his effort and his mark, even though the mission did not succeed. It is well deserved that he is still a legend in his family, known by the English nick name "Lawyer".

Sources (mostly in Danish)

P. Zoffmann, Sct. Jørgens Hospital i Kolding 1558-1958, Konrad Jørgensens Bogtrykkeri, Kolding 1958.

P. Eliassen, Det gamle og nyere Kolding, Konrad Jørgensens Bogtrykkeri, Kolding 1910.

C. Chr. Lausen Utzon, Familien Utzon, Konrad Jørgensens Bogtrykkeri, Kolding 1907.

N.A. Kjær, 25 Aar i Vestindien. Fra Firsernes og Halvfemsernes St. Thomas, A. Rosenbergs Bogtrykkeri, København 1934.

Et Foredrag om de dansk-vestindiske Øer, holdt af Prokurator, Overformynder Jørgensen. Carl Mar: Møllers Bogtrykkeri, Horsens 1902.

Betænkning afgiven af den i Henhold til Lov Nr. 294 af 30. September 1916 nedsatte Rigsdagskommission angaaende de dansk vestindiske Øer, J.H. Schultz A/S, København 1916, bilag B., pp. 290-315.

Ordenskapitlets biografiarkiv.

The Jørgensen family's own notes, recollections, photos and letters. A collection of private letters in the Royal Library in Copenhagen. All facilitated by Karin Aae Evensen (1941-2012), great-great-granddaughter of Lawyer Jørgensen. Without her assistance, this article would not have been written.

The Jochimsen family's letter archive, facilitated by Halvor Jochimsen, Julius Jochimsen's grandchild. The part of the letter archive that has been used in this article is in German and English. It has now been delivered to Staatsarchiv Hamburg and registered with other records concerning HAPAG-Lloyd.

A few letters after Carl Emil Hassager, managing director for East Asiatic Company in St. Thomas 1905-16, facilitated by his grandchild Peter Kelstrup.

Danish West Indies Society's periodical (www.dwis.dk), miscellaneous issues.

Public reference books and parish records.

A special thanks to the chairman of Danish West Indian Society Anne Walbom and to Dante Beretta for valuable source references and other assistance. In addition, I thank Dante Beretta for his essential corrections and comments to the present translated version of the article.

Notes:

[1] This portrait is the original reason for

me to take an interest in Lawyer Jørgensen. The painting was inherited in Hugo Larsen's family, the sole

information being that it might portray a Lissa Jørgensen. In 2003 while researching the St. Thomas

historical newspapers I bumped into a possible connection between Lawyer Jørgensen and a Miss

Elizabeth Jørgensen. I decided to research the family which led me to descendants of Lawyer

Jørgensen who were able to recognize Lissa Jørgensen in the portrait and owned the photo of the

10 years older Lissa, then married to Heinrich Meyn and mother of Jens Peter Meyn.

to note reference 1

[2] This photo of Lawyer Jørgensen and medical

doctor Viggo Christensen is probably the last one portraying Jørgensen. The old friends from St. Thomas

have probably been invited for christmas in Villa Mafolie in Aarhus by Jørgensen's oldest daughter

Henriette, married Aae. Dr. Viggo Christensen was among the Danes who stayed in the islands after the

Transfer. He was brother-in-law to Julius Jochimsen and inventor of the new name for the islands, US

Virgin Islands.

to note reference 2